Director Shawn Seet about STORM BOY

“When in panic, use a red bucket.” In a contemporary version of the classic Australian tale STORM BOY, Michael - the original Storm Boy from the 1976 feature film of the same name – has grown up to become a retired businessman and grandfather. When remembering his long-forgotten childhood, growing up on an isolated coastline, Michael, to his granddaughter, recounts the story of how, as a boy, he rescued and raised an orphaned pelican, Mr Percival. Storm Boy’s adventures are now re-told in a beautiful film, that is the rightful opener of this year’s Zlin Film Festival.

Director Shawn Seet: “I’m truly honoured to have this film just be a part of this Festival, let alone be the opening film. I hope that everyone will connect with the themes of the film which I believe are universal, and experience the beauty and wildness of the Coorong National Park, a unique environment in Australia and the world.”

Colin Thiele’s novella Storm Boy, telling the story of a young boy’s extraordinary friendship with a pelican, has enchanted Australians for over half a century. Australian children still study the book at school, and in 2013 a stage adaptation was sold out for the entire season. That’s when producer Matthew Street got the idea that maybe it was time for a cinematic re-adaptation.

Producer Matthew Street: I was probably the age of Storm Boy when I saw this film, that deals with life issues that were relatable to me. We recognised that the themes of Thiele’s 1963 book are just as relevant, and in some ways more so, today.

Director Shawn Seet: The current youth protest movement makes the context of this film even clearer. When I look at my children and their generation, I feel two things. One is a sense of worry about what kind of world we are leaving them to inherit but the other stronger feeling is one of optimism because I know that the youth are the great hope for all of us. When I see their worldwide consciousness in these protests, I know this optimism is well-founded. This film was always intended to energise and empower young people to feel they can and will make a difference. You can save three pelicans and you can save the planet. As Geoffrey Rush says in the film, “It’s up to you now”.

You felt a strong personal bond with this story.

Seet: I grew up in Malaysia and came back to Australia when I was 12. My uncle educated me by taking me to see Australian films and one of the first he took me to was STORM BOY. I still have the film poster at home, so when I heard about making this film, I felt it was meant to be. I made the film with new audiences in mind. I wanted to connect with young people today and bring them this beautiful story in a form that they would find relevant. But I also wanted people of my generation to appreciate it, people who knew the story and loved the 1976 classic. I hope that older audiences will reconnect with their childhood through this film and be able to see it through young eyes, and that after it young and old will understand one another a little better.

Indigenous people from the Coorong region were involved in the filming process.

Seet: The participation of the Ngarrindjeri would be vital, as the film is set on their land, and represents their culture. The pelican is a totem of the Ngarrindjeri. The film touches on land rights issues and that’s incredibly relevant today, as we’ve still got a long way to go in terms of our relationship with Indigenous people. A story about living in harmony with the land and with nature could not be told accurately without their help. It was very important to the Ngarrindjeri people to grant permission for us to film on the Coorong. I think they knew that we would be respectful to their ways and beliefs.

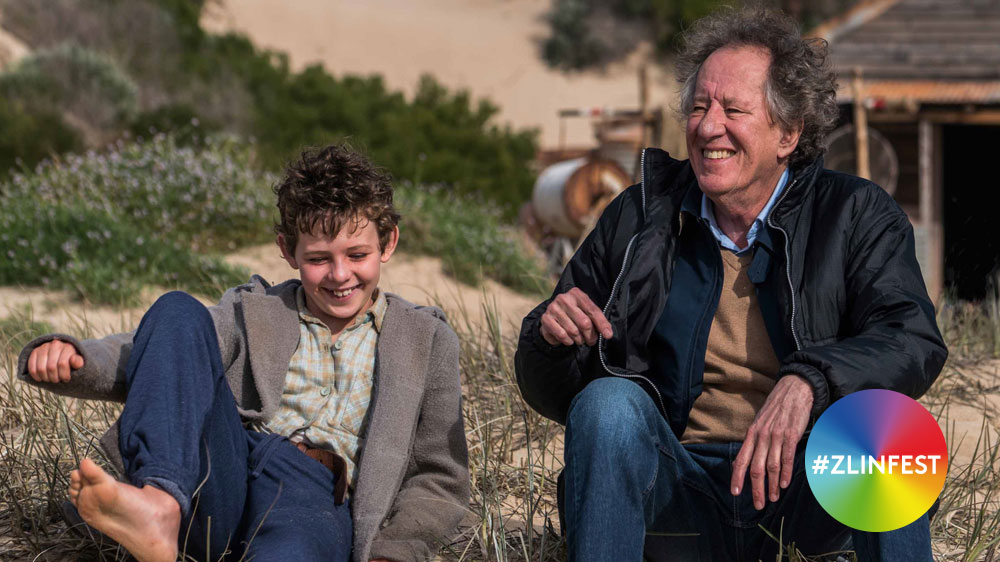

Oscar winner Geoffrey Rush (THE KING’S SPEECH, PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN) was born for his role as Michael Kingley. Did he realize that or did you have a hard time convincing him?

Seet: I think he felt that right away. But Geoffrey does not take on any role lightly and we spent time together working through the script and talking about the way I intended to realise it until he was comfortable that this was right for him. It was not a hard time as such, Geoffrey is such an intelligent collaborator. If he had decided not to take the role (and I am so grateful that he did) then the work we had done would still give me very valuable insights into the role and the script.

Working with pelicans was a challenge, intrinsically linked to the making of this film.

Street: The producers hired a highly-experienced animal supervisor and bird trainer to find, raise and train the birds. Pelicans have a long life span but a high mortality rate in the wild, partly due to predators such as foxes. Five birds were found, rescued and reared.

How were they trained?

Seet: With food rewards. Every time they did a desired behaviour, they got a fish. Pelicans have very good memory retention, so what they learn carries over into the next day. Animal trainers need to know a certain amount of theory, but they need to be compassionate and understanding, trying to make the animal understand what it is we’re trying to achieve.

It was crucial to get young actor Finn Little working with these remarkable birds.

Seet: Finn first met the birds when they were just six weeks old. Each week, he would come and do bonding sessions, spending time with them, so that they would associate him as being friendly and part of the group. The birds formed a strong affinity with Finn and vice-versa.

Could you cast the birds for individual roles?

Seet: Working out how the five birds would portray the three characters Mr Proud, Mr Ponder and Mr Percival was very similar to casting any role. Pelicans all have very strong and distinct characters, and they all developed very distinct tricks. Some were good at hide and seek, some were good at flying, so we could pick and choose who did what. One male bird, Salty, was adept at working up close with Finn and so he primarily represents Mr Percival on screen.

Did they test your flexibility?

Street: Cast and crew were surprised every day by the birds’ improvisations. We had to adapt the script to their performances. These are personalities, and they brought so much more to it. We only used CGI pelicans in a very few limited specific moments. Basically everything you see was real and it was spectacular.

Seet: When brought to set, Salty would run along and brush up against the crew one by one, as if saying hello. Nothing restrained them on set, so at unexpected moments they would fly away. In case of emergency, we used ‘the red bucket’. That was their strong visual sign that they were going to get more than one fish.

Where are they now?

Street: They’re now homed in several places, like the Adelaide Zoo, where they’ll live out their lives with great enjoyment. They haven’t had to survive the rigours of nature.

You did most of the shooting near the water, at the seaside. Did that cause extra logistical or technical challenges?

Seet: The area we shot in was where Colin Thiele had set his novella. It is completely remote and only accessible by boat. This was both a challenge and a blessing. Everything had to be transported there. Water had to be transported for the rain effects, power had to be supplied by a generator, we had to build the shack and the jetty from scratch. So we could design it to be exactly as we needed for shooting. And then there was the weather, which we were at the mercy of. It could be sunny one minute and then stormy and raining the next. It was fortunate that we had scenes that were meant to be stormy. It just meant that we had to be flexible and switch to shooting a different scene at a moment’s notice if the weather changed. The great blessing of shooting there came as part of its remoteness. The half hour boat trip every day at dawn was like a trip in a time machine to a different world. By the time we arrived at the location, everyone, cast and crew, was in a different head space. We were completely immersed in the magical world we were there to capture. It energized us and our work and I am sure you can see it in the film.

Imagine you could fill the cinema with the perfect audience for your film, and you could invite whoever you wanted to come and see STORM BOY, who would be in that cinema?

Seet: At the risk of sounding arrogant enough to think that one film can change the world, I would love to invite all the leaders of governments and the heads of big industries and see if they remember what it’s like to be young and to see beauty in all that surrounds them and maybe they would think twice before commissioning another mine or coal-powered station. On a more personal note, I would love to invite Colin Thiele to see film I made from his story and hear what he thinks of it.

Sounds like a perfect Zlin Festival screening!